Copper——Sources of Exposure; Industrial Hygiene and Risk Assessments

First aid: Inhalation: Remove to fresh air. Provide respiratory support. Ingestion: Induce vomiting immediately as directed by medical personnel. Skin: Immediately flush skin with plenty of soap and water for at least 15 min. Remove contaminated clothing and shoes. Eye contact: Immediately flush eyes with plenty of water for at least 15 min. Get medical attention immediately.

Target organ(s): Eyes, skin, respiratory system, liver, kidneys (increased risk with Wilson’s disease)

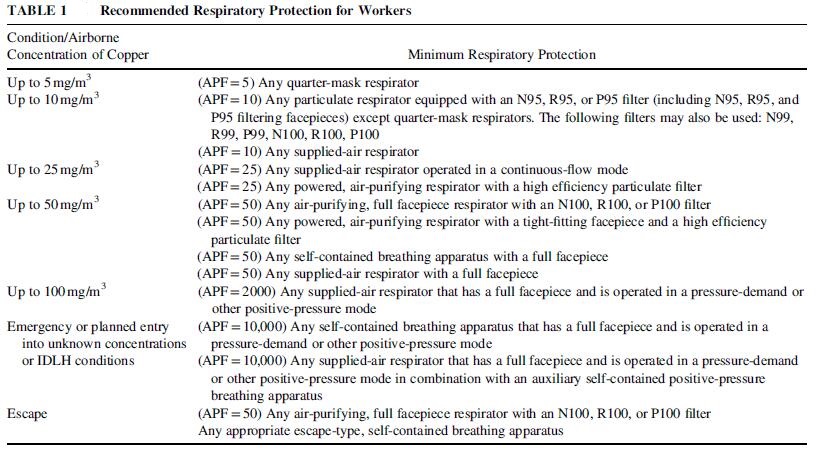

Occupational exposure limits: NIOSH REL: TWA 1 mg/m3, OSHA PEL: TWA 1 mg/m3 and ACGIH TLV: TWA 1 mg/m3 [REL, PEL, and TLV also apply to other copper compounds (as Cu) except copper fume], TLV 0.2 mg/m3 (fume), NIOSH IDHL: 100 mg/m3

Reference values: MRL: 0.01 mg/kg/day (oral)

Risk phrases: 11-36/37

Flammable: Irritating to eyes and respiratory system

Safety phrases: 26-60

In case of contact with eyes, rinse immediately with plenty of water and seek medical advice. This material and/or its container must be disposed of as hazardous waste.

SOURCES OF EXPOSURE

Exposure to copper in humans can occur through inhalation, ingestion, and eye or skin contact (IPCS, 1998; HSDB, 2007b).

Occupational

Copper exposure is common in occupations, including asphalt makers, electroplaters, wallpaper makers and embossers, solderers, especially miners and smelters of copper ore (ATSDR, 2004). The major industrial route of exposure to copper is inhalation of dust and fumes. Dermal contact and ingestion are less likely to cause adverse effects in an occupational setting (Weir, 1979). The salts of copper generally are considered more toxic than copper dust and fumes, which are relatively nontoxic. The vaporization point of copper is high (about 2350 °C [4262 °F]), and it is rare to encounter these fumes in industry.

Another hazard in copper mining is concurrent exposure to more hazardous metals and compounds. Exposure to arsenic, selenium, lead, and cadmium is associated with copper mining. Industrial hygiene measures are more appropriately tailored to these more hazardous materials than to the copper present. Respiratory protection with face masks and adequate ventilation is recommended in mining operations to protect against exposure to dust and fumes. Protective clothing should be worn, and the skin should be washed after a work shift to reduce dermal contact.

Environmental

Copper is environmentally ubiquitous. The general population may be exposed to copper through the ingestion of drinking water and foods, contact with copper-containing soil, and inhalation of air tainted with copper (HSDB, 2007). Copper concentrations in drinking water range from 20 to 75 ppb and drinking water is the greatest potential exposure source. They may be substantially higher in homes with copper piping/fixtures or lower pH water. Soils, sediments, and dusts commonly contain copper and copper compounds. Many foods, particularly organ meats and mollusks, also contain significant amounts of copper.

INDUSTRIAL HYGIENE

The current Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) recommended exposure limit(PEL), NIOSH recommended exposure limit(REL), and American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) threshold limit value(TLV) for copper are 1 mg/m3 as an 8-h time-weighted average (TWA) concentration. This applies to other copper compounds except copper fume. The OSHA PEL and NIOSH REL for copper fume are 0.1 mg/m3 as an 8-h (TWA) concentration, and the ACGIH TLV is 0.2 mg/m3. Recommendations by NIOSH on respiratory protection for workers exposed to copper are listed in Table 1.

RISK ASSESSMENTS

No chronic reference dose (RfD) or reference concentration (RfC) for copper is currently available on EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) or in the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories. There are no human carcinogenicity data and inadequate animal data from assays of copper compounds.

REFERENCES

Johncilla, M. and Mitchell, K.A. (2011) Pathology of the liver in copper overload. Semin. Liver Dis. 31(3):239–244. Kumar, N., Elliott, M.A., Hoyer, J.D., Harper, C.M., Jr.,Ahlskog, J.E., and Phyliky, R.L. (2005) “Myelodysplasia,” myeloneuropathy, and copper deficiency. Mayo Clin. Proc. 80(7): 943–946.

Lightfoot, N.E., Pacey, M.A., and Darling, S. (2010) Gold, nickel and copper mining and processing. Chronic Dis. Can. 29(Suppl. 2):101–124.

Muller, T., Muller, W., and Feichtinger, H. (1998) Idiopathic copper toxicosis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 67(Suppl. 5):1082S–1086S.

NIOSH (2010) Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards: Copper Dusts and Fumes, Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Ostiguy, G., Vaillancourt, C., and Bégin, R. (1995) Respiratory health of workers exposed to metal dusts and foundry fumes in a copper refinery. Occup. Environ. Med. 52(3):204–210.

You may like

Related articles And Qustion

See also

Lastest Price from Copper manufacturers

US $0.00-0.00/kg2025-12-09

- CAS:

- 7440-50-8

- Min. Order:

- 1kg

- Purity:

- 98%

- Supply Ability:

- 1000kg

US $6.00/kg2025-04-21

- CAS:

- 7440-50-8

- Min. Order:

- 1kg

- Purity:

- 99%

- Supply Ability:

- 2000KG/Month