Adverse effect of D-mannose

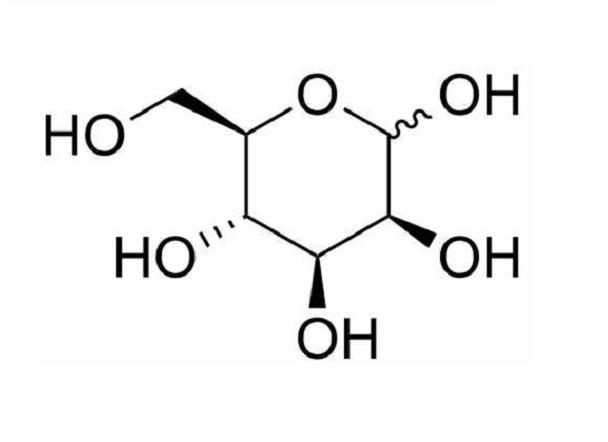

D-mannose (or mannose) is a type of sugar found in a number of fruits and vegetables, including cranberries, black and red currants, peaches, green beans, cabbage, and tomatoes. It's also produced in the body from glucose, another form of sugar. D-Mannose is the 2-epimer of glucose and exists primarily as sweet-tasting α- (67%) or as a bitter-tasting β- (33%) anomer of the pyranose; furanose forms comprise <2%. Mannose is ~5x as active as glucose in non-enzymatic glycation, which may explain why evolution did not favor it as a biological energy source [1-3]. In the laboratory, mannose can be generated by oxidation of mannitol or by base-catalyzed epimerization of glucose through fructose. L-Mannose is not normally used in biological systems; however, its structural similarity to naturally occurring L-rhamnose enables some plant enzymes to use L-mannose as an unnatural substrate in vitro. Mutant strains of A. aerognees can use it as a sole carbon and energy source [1-3].

Figure 1 the molecular formula of mannose

Existence

Mannose occurs in microbes, plants and animals. Free mannose is found in small amounts in many fruits such as oranges, apples and peaches and in mammalian plasma at 50–100 μM More often, mannose occurs in homo-or hetero-polymers such as yeast mannans (α-mannose) where it can account for nearly 16% of dry weight or in galactomannans. Ivory nuts, composed of β-mannans (sometimes called vegetable ivory) are quite hard and used for carving and manufacturing buttons. In fact, ivory nut shavings were the original industrial source of mannose. Coffee beans, fenugreek and guar gums are rich sources of galactomannans [4], but these plant polysaccharides are not degraded in the mammalian GI tract and, therefore, provide very little bio-available mannose for glycan synthesis. These polysaccharides are partially digested by anaerobic bacteria in the colon [5]. Small amounts of bio-available mannose occur in glycoproteins.

Mannose metabolism in vivo

Mannose is transported into mammalian cells via facilitated diffusion hexose transporters of the SLC2A group (GLUT) present primarily on the plasma membrane. Various cell lines transport 6.5 – 23.0 nmols/hr/mg protein [6], but no mannose-specific or -preferential transporters have been reported among the 14 distinct GLUT transporters found in humans [7]. Most studies of GLUT substrate specificity assess only transport of glucose and fructose, but very rarely mannose transport. Several reports describe SGLT-like mannose transporters in the intestine and kidney, where they could deliver free mannose from the diet or recover it from the urine [8]. To date, there is no evidence for the physiological importance of these transporters. Within the cell, mannose is phosphorylated by hexokinase (HK) to produce mannose-6-phosphate (Man-6-P), which serves as a common substrate for three competing enzymes. It is either catabolized by phosphomannose isomerase (MPI) or directed into N-glycosylation via phosphomannomutase (PMM2). Another minor pathway utilizes mannose for synthesis of 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galacto-nononic acid (KDN), a sialic-acid related molecule found in fish and mammals [9]. The fate of Man-6-P largely depends on the ratio of MPI to PMM2 within a cell [6] - higher ratio leads to greater catabolism, while lower ratio favors the glycosylation pathway. PMM2-derived mannose-1-phosphate (Man-1-P) is then incorporated into several glycosylation intermediates including GDP-mannose (GDP-Man), GDP-fucose, and dolichol phosphate mannose (Dol-P-Man). These intermediates then contribute to N-glycosylation, O- glycosylation, C-mannosylation, and GPI anchor synthesis.

Mannose is the major monosaccharide component of N-glycans and relies on ample supply of Man-6-P, Man-1-P, GDP-Man, and Dol-P-Man for synthesis of lipid linked oligosaccharides (LLO). The first five mannose residues are added on the cytoplasmic face of ER using GDP-Man. The glycan is then flipped to the luminal side via a flippase [10] and extended by four more mannose residues and glucose. This Man9Glc3GlcNAc2 glycan is transferred to newly synthesized proteins soon after they emerge from the translocon or somewhat later [11]. A variable portion of LLO can also be hydrolyzed producing free oligosaccharides. Protein-bound N-glycans can undergo extensive mannose trimming, liberating free mannose within the ER and Golgi. Misfolded glycoproteins in the ER that fail to pass quality control are retro translocated into the cytoplasm and stripped of their glycans, which are further degraded in the cytoplasm and lysosome yielding free mannose [12].

Application and health benefit

As a dietary supplement, D-mannose is often touted as a natural way to treat and prevent a urinary tract infection (UTI) or bladder infection (cystitis). Though more research is needed, preliminary studies suggest that the supplement could be well worth exploring. Since treatment for frequent UTIs is long-term low-dose antibiotic use (six months or longer),[13] having a non-antibiotic treatment for this type of infection—which accounts for more than six million healthcare provider visits a year—would help prevent antibiotic resistance.

A series of studies have suggested that D-mannose may hinder bacteria from adhering to the cells lining the urinary tract. D-mannose can help stop E. coli (the bacteria responsible for the vast majority of UTIs) from sticking to cells in the urinary tract.[14] A study published in the World Journal of Urology in 2014 examined the use of D-mannose to prevent recurrent urinary tract infections. After one week of initial treatment with antibiotics for an acute UTI, 308 women with a history of recurrent UTIs took D-mannose powder, the antibiotic nitrofurantoin, or nothing for six months [15].

During the six-month period, the rate of recurrent UTIs was significantly higher in women who took nothing compared to those who took D-mannose or nitrofurantoin. Fewer side effects were reported with D-mannose compared to the antibiotic. The main one noted was diarrhea, which occurred in 8% of women taking D-mannose.

A small pilot study of 43 women published in 2016 found that D-mannose administered twice daily for three days followed by once a day for 10 days resulted in a significant improvement in symptoms, UTI resolution, and quality of life. Those who received D-mannose for six months following treatment had a lower rate of recurrence than those who took nothing [16].

Although D-mannose shows promise, a review of studies published in 2015 concluded that D-mannose (and other non-pharmaceutical remedies like cranberry juice and vitamin C) are ill-suited to replace antibiotics in treating UTIs [17].

Adverse effect

Common side effects of D-mannose include bloating, loose stools, and diarrhea. As D-mannose is excreted from the body in urine, there is also some concern that high doses may injure or impair the kidneys. Since D-mannose can alter your blood sugar levels, it's crucial for people with diabetes to take caution when using D-mannose supplements. Not enough is known about the safety of the supplement during pregnancy or breastfeeding, so it should be avoided. Children shouldn't take D-mannose as well. As a rule, self-treating a UTI with D-mannose, or avoiding or delaying standard care, is unadvised as it can lead to serious complications, including a kidney infection (pyelonephritis) and even permanent kidney damage.

References

1. G. Mersmann, K. Von Figura, E. Buddecke, Storage of mannose-containing material in cultured human mannosidosis cells and metabolic correction by pig kidney alpha-mannosidase, Hoppe. Seylers. Z. Physiol. Chem. 357 (1976) 641–648.

2. R. Niehues, M. Hasilik, G. Alton, C. Körner, M. Schiebe-Sukumar, H.G. Koch, et al., Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type Ib. Phosphomannose isomerase deficiency and mannose therapy, J. Clin. Invest. 101 (1998) 1414–1420.

3. B. Kranjcˇec, D. Papeš, S. Altarac, D-mannose powder for prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: a randomized clinical trial, World J. Urol. 32 (2014) 79–84.

4. M. Srivastava, V.P. Kapoor, Seed galactomannans: an overview, Chem. Biodivers 2 (2005) 295–317.

5. J. Tan, C. McKenzie, M. Potamitis, A.N. Thorburn, C.R. Mackay, L. Macia, The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Health and Disease, Adv. Immunol.121 (2014) 91–119.

6. V. Sharma, H.H. Freeze, Mannose efflux from the cells: a potential source of

mannose in blood, J. Biol. Chem. 286 (2011) 10193–10200.

7. M. Mueckler, B. Thorens, The SLC2 (GLUT) family of membrane transporters, Mol. Aspects Med. 34 (2013) 121–138.

8. M.C. De la Horra, M. Cano, M.J. Peral, M. García-Delgado, J.M. Durán, M.L. Calonge, et al., Na (+)-dependent D-mannose transport at the apical membrane of rat small intestine and kidney cortex, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1512 (2001) 225–230.

9. S. Go, C. Sato, K. Furuhata, K. Kitajima, Oral ingestion of mannose alters the expression level of deaminoneuraminic acid (KDN) in mouse organs, Glycoconj. J. 23 (2006) 411–421.

10. S. Sanyal, A.K. Menon, Specific transbilayer translocation of dolichol-linked oligosaccharides by an endoplasmic reticulum flippase, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106 (2009) 767–772.

11. M. Aebi, N-linked protein glycosylation in the ER, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833 (2013) 2430–2437.

12. A. Helenius, Intracellular functions of N-linked glycans, Science 291 (2001) 2364–2369.

13. Ahmed H, Davies F, Francis N, Farewell D, Butler C, Paranjothy S. Long-term antibiotics for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5): e015233.

14.Wellens A, Garofalo C, Nguyen H, et al. Intervening with urinary tract infections using anti-adhesives based on the crystal structure of the FimH-oligomannose-3 complex. PLoS One. 2008;3(4): e2040.

15.Kranjčec B, Papeš D, Altarac S. D-mannose powder for prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: a randomized clinical trial. World J Urol. 2014;32(1):79-84.

16.Domenici L, Monti M, Bracchi C, et al. D-mannose: a promising support for acute urinary tract infections in women. A pilot study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(13):2920-5.

17. Aydin A, Ahmed K, Zaman I, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Recurrent urinary tract infections in women. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(6):795-804.

You may like

Related articles And Qustion

See also

Lastest Price from D-Mannose manufacturers

US $0.00-0.00/g2025-06-06

- CAS:

- 3458-28-4

- Min. Order:

- 1g

- Purity:

- 99%

- Supply Ability:

- 10000tons

US $10.00/Kg2025-04-24

- CAS:

- 3458-28-4

- Min. Order:

- 1Kg

- Purity:

- 98%

- Supply Ability:

- 20Ton