Ethanol: The preparation, application and toxicity

General description

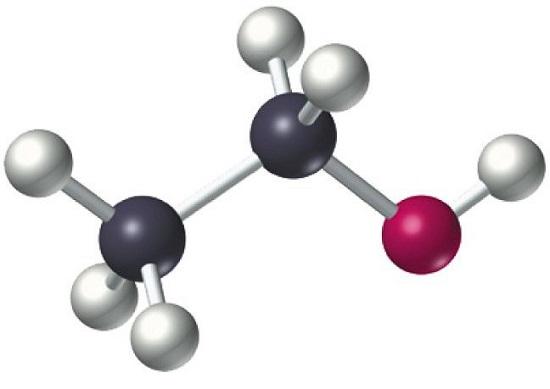

Ethanol (alcohol, ethyl alcohol) is widely available as a beverage, is an important constituent of cosmetics, aftershave, hair tonic, antiseptics, mouthwashes, dishwashing detergents and glass cleaners, and is commonly used as an industrial solvent. Ethanol burns in air with a blue flame, forming carbon dioxide and water. It reacts with active metals to form the metal ethoxide and hydrogen, e.g., with sodium it forms sodium ethoxide. It reacts with certain acids to form esters, e.g., with acetic acid it forms ethyl acetate. It can be oxidized to form acetic acid and acetaldehyde. It can be dehydrated to form diethyl ether or, at higher temperatures, ethylene. The appearance of Ethanol is as follows:

Figure 1 Appearance of Ethanol.

Preparation

Ethanol is the alcohol of beer, wines, and liquors. It can be prepared by the fermentation of sugar (e.g., from molasses), which requires an enzyme catalyst that is present in yeast; or it can be prepared by the fermentation of starch (e.g., from corn, rice, rye, or potatoes), which requires, in addition to the yeast enzyme, an enzyme present in an extract of malt [1]. The concentration of ethanol obtained by fermentation is limited to about 10% (20 proof) since at higher concentrations ethanol inhibits the catalytic effect of the yeast enzyme. (The proof concentration of an alcoholic beverage is numerically double the percentage concentration.) For nonbeverage uses ethanol is more commonly prepared by-passing ethylene gas at high pressure into concentrated sulfuric or phosphoric acid to form the corresponding ester; the acid-ester mixture is diluted with water and heated, forming ethanol by hydrolysis, and the alcohol is then removed from the mixture by distillation, usually with steam.

Application

Ethanol is used extensively as a solvent in the manufacture of varnishes and perfumes; as a preservative for biological specimens; in the preparation of essences and flavorings; in many medicines and drugs; as a disinfectant and in tinctures (e.g., tincture of iodine); and as a fuel and gasoline additive (see gasohol). Many U.S. automobiles manufactured since 1998 have been equipped to enable them to run on either gasoline or E85, a mixture of 85% ethanol and 15% gasoline. E85, however, is not yet widely available [2]. Denatured, or industrial, alcohol is ethanol to which poisonous or nauseating substances have been added to prevent its use as a beverage; a beverage tax is not charged on such alcohol, so its cost is quite low. Medically, ethanol is a soporific, i.e., sleep-producing; although it is less toxic than the other alcohols, death usually occurs if the concentration of ethanol in the bloodstream exceeds about 5%. Behavioral changes, impairment of vision, or unconsciousness occur at lower concentrations.

Toxicity

Acute ethanol poisoning is an uncommon cause of adult death; when fatalities occur, aspiration of gastric contents is an important factor. More often, ethanol potentiates the effects of other drugs taken in overdose. However, ethanol intoxication is an important cause of accidental death in children under 5 years of age. Children may be forced to drink alcohol under duress, and this may be associated with sexual abuse. In young children who have not eaten for 8–12 hours, ingestion of even modest amounts of ethanol (e.g. the dregs left after a party) may lead to permanent neurological damage as a result of hypoglycaemia [3].

Ethanol is absorbed rapidly through the gastric and small intestinal mucosae [4]. Peak blood ethanol concentrations usually occur within 30–90 minutes of ingestion. Gastric alcohol dehydrogenase isoenzyme has a role in metabolizing ethanol before absorption, thereby preventing ethanol entering the systemic circulation, particularly following ingestion of moderate amounts of alcohol [5]. Absorbed ethanol is initially and principally converted to acetaldehyde by an nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase. About 95% of ingested ethanol is oxidized to acetaldehyde and acetate. Acetaldehyde, which is toxic, is removed by oxidation via the (oxidized) NAD-dependent enzyme, aldehyde dehydrogenase, to yield acetate and, subsequently, carbon dioxide and water.

At high blood concentrations (>1000 mg/L) ethanol is eliminated by zero-order kinetics (i.e. the rate of elimination is constant regardless of concentration), so that ethanol concentrations can be expected to decrease at a constant rate of 60–400 mg/ L/hour (usually 150 mg/L/hour). Regular social drinkers tend to have higher ethanol elimination rates than non-drinkers, but ethanol abusers with severe liver damage usually eliminate ethanol more slowly [4].

References

[1]Ballinger P, Long FA (1960). Acid Ionization Constants of Alcohols. II. Acidities of Some Substituted Methanols and Related Compounds1,2. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 82 (4): 795–798.

[2]Scalley R (September 2002). Treatment of Ethylene Glycol Poisoning. American Family Physician. 66 (5): 807–813.

[3]Allister (2007). Medicine, 1997, 35(11): 615-616.

[4]Norberg A?, Jones Wa, Hahn RG, Gabrielsson JL (2003). Role of variability in explaining ethanol pharmacokinetics: research and forensic applications. Clin Pharmacokinet, 42: 1–31.

[5]Haber Ps (2000). Metabolism of alcohol by the human stomach. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 24: 407–8.

You may like

Related articles And Qustion

See also

Lastest Price from Ethanol manufacturers

US $0.00/kg2025-11-28

- CAS:

- 64-17-5

- Min. Order:

- 1kg

- Purity:

- 98%

- Supply Ability:

- Customise

US $10.00/kg2025-06-26

- CAS:

- 64-17-5

- Min. Order:

- 1kg

- Purity:

- 99.5%

- Supply Ability:

- 100 TON