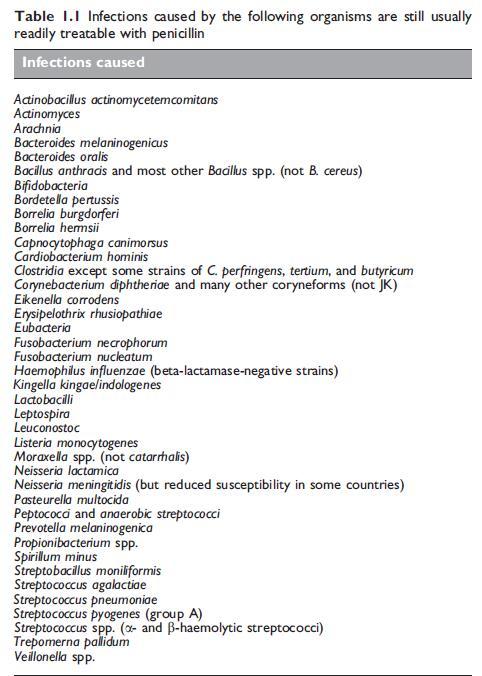

Clinical Uses of Penicillin G

Pen G remains a very effective treatment for infections caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (which have not, to date, developed resistance to penicillin), such as pharyngitis, scarlet fever, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, septic arthritis, uterine infection, and septicemia. In recent years, septicemia in children and young adults has often been very severe with multisystem involvement and shock (Jackson et al., 1991; Stevens, 1992; Demers et al., 1993). A changing nature of septicemia has also been observed since 1988. Since that time, a toxic shock-like syndrome has occurred in 8% of invasive infections in some series. Adults with this syndrome were younger than patients with other invasive infections. These patients were similar in some ways to those with S. aureus toxic shock syndrome. They showed hypotension, erythematous rash, desquamation, and renal and gastrointestinal manifestations and septic thrombophlebitis. The blood cultures were positive in some 60% of cases and the mortality was approximately 30% (Cohen-Abbo and Harper, 1993; Hage et al., 1993; Shulman, 1993; Jevon et al., 1994). In general, there was a lower rate of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and lower mortality in children with invasive group A streptococcal infections than in young adults (Davies et al., 1994).

For severe infections, i.m. or i.v. crystalline Pen G in a dose of 0.6– 1.8 g every 3–6 hours is required for adults. Mild to moderate streptococcal pharyngitis in children and adults can be treated satisfactorily by a single i.m. injection of benzathine Pen G (adult dose 1.2 million units or 0.9 g). When shorter-acting preparations are used, treatment should be for at least 10 days in an endeavor to eradicate the organisms from the pharynx, and to prevent subsequent rheumatic fever (Peter and Smith, 1977; Peter, 1992).

Group B streptococcal infections

Pen G is the drug of choice for treatment of all of these infections, and most cases require parenteral therapy with crystalline Pen G (MMWR, 2002; Gibbs et al., 2004). In neonates, the high dose as recommended for meningitis should be used (see Table 1.7). A recent study concluded that in very low-birth weight infants a penicillin dose of 25,000 IU (15 mg)/kg every 12 hours is safe and sufficient to achieve serum concentrations above the MIC90 for GBS for the entire dosing interval (Metsvaht et al., 2007).

Combination therapy using Pen G plus an aminoglycoside, such as gentamicin, may be more effective, but one study in animals showed that Pen G plus gentamicin was about as effective as Pen G alone (Kim, 1987). However, this combination is generally necessary for all severe neonatal infections before the organism is identified (Leading article, 1979). On theoretical grounds, combination therapy should be valuable if the infecting organism is a Pen G-tolerant group B streptococcus, but this has not been studied by controlled trials (Siegel et al., 1981).

Group C, G, F and R streptococcal infections

These are less common human pathogens. Group C streptococci occasionally cause pharyngitis, skin and wound infections, female genital tract infections, endocarditis, and septicemia (Bradley et al., 1991). Group G streptococci may cause infections such as endocarditis, septicemia, meningitis, cellulitis, septic arthritis, wound infections, cholangitis, pneumonia, and peritonitis (Fujita et al., 1982; Auckenthaler et al., 1983; Craven et al., 1986; Venezio et al., 1986; Ashkenazi et al., 1988). Infections by these two pathogens have often occurred in patients with underlying debilitating conditions such as alcoholism, drug abuse, and malignancy. Pen G is the optimal treatment for groups C and G streptococcal infections. For severe group G streptococcal infections, such as endocarditis, a Pen G– aminoglycoside combination may be superior (Vartian et al., 1985). Group F streptococci rarely cause abscesses and septicemia. Again, Pen G is the treatment of choice (Libertin et al., 1985).

Pneumonia in adults

For pneumococcal lobar pneumonia, Pen G is an effective treatment. Even if disease due to pneumococcal strains with a very high degree of resistance to Pen G is encountered, high-dose Pen G is usually effective unless there is associated meningitis (Klugman, 1994; Pallares et al., 1995; Jernigan et al., 1996; Plouffe et al., 1996). Pneumococcal infection remains the most common cause of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) (Holmberg, 1987; Davies and Jolley, 1992; Marrie, 1994; BTS, 2001; Macfarlane and Boldy, 2004; Charles et al., 2008). Other bacterial causes of such pneumonia are Legionella pneumophila, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and E. coli. Atypical bacterial causes of CAP include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia psittaci, C. pneumophila, Coxiella burnetti, and viruses, mainly influenza (Lode, 1986; Charles et al., 2008). A summary of recommended therapies for pneumonia in adults is shown in Table 1.11. Every effort should be made to make an immediate diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia so that monotherapy with Pen G can be given and the administration of multiple antibiotics avoided.

Childhood respiratory tract infections

Most childhood community-acquired bacterial pneumonias are pneumococcal and respond well to Pen G. However, in children, many radiologically confirmed pneumonias are caused by viruses or Mycoplasma pneumoniae. In one study of radiologically confirmed pneumonias, S. pneumoniae caused 38%, respiratory syncytial virus 30%, and M. pneumoniae 20% (Ruuskanen et al., 1992). Therefore, all modern diagnostic techniques should be used at the outset so that Pen G is not used for viral infections, and erythromycin is correctly prescribed for Mycoplasma infections. Rarer bacterial causes of pneumonia in this age group are H. influenzae type b and S. aureus, and drugs other than Pen G are necessary for these. In lung abscess and aspiration pneumonia, antibiotics similar to those recommended for adults should be used (see above under 7.4. Pneumonia in adults).

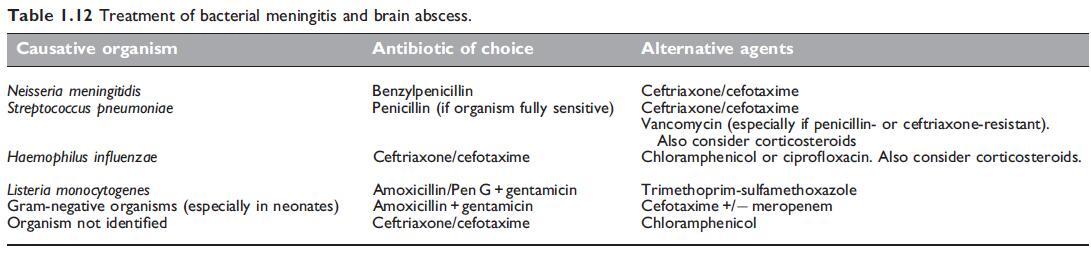

Bacterial meningitis

Despite the availability of several third-generation cephalosporins which are effective for the treatment of bacterial meningitis (e.g. ceftriaxone), Pen G still remains an important antibiotic for this disease, especially in developing countries. With the exception of neonatal meningitis, a combination of Pen G and chloramphenicol was commonly used for the empiric treatment (before the organism was identified) of acute bacterial meningitis in many developing countries. This initial therapy covered nearly all causal organisms, but, once the organism was identified, Pen G alone was the drug of choice for meningococcal and pneumococcal meningitis (Geiseler et al., 1980; Sangster et al., 1982) and chloramphenicol for H. influenzae meningitis. Indeed, chloramphenicol alone may be used for initial therapy as it is equally as effective as Pen G for the treatment of meningococcal and pneumococcal meningitis. This classical chemotherapy is used widely in developing countries where the third-generation cephalosporins are too expensive. A summary of treatment protocols for bacterial meningitis due to a variety of pathogens is shown in Table 1.12.

Brain abscess

Pen G is an important antibiotic for the treatment of cerebral abscess.

Frontal lobe abscesses arising from the sinuses may respond to Pen G

alone, as they are usually caused by various types of Pen G-sensitive

streptococci, such as S. milleri. Abscesses of otitic origin which occur in

the temporal lobe usually yield a mixed flora often including anaerobic

bacteria – for these Pen G should be combined with metronidazole (or

chloramphenicol). Metastatic abscesses which occur anywhere within

the brain can be caused by streptococci, staphylococci, or by a variety

of other bacteria. Combination therapy, including an effective antistaphylococcal

drug, is necessary until bacteriologic results are

available.

Meningococcal and pneumococcal

septicemia.

Pen G is the best drug for treatment of meningococcal septicemia, which can either be mild with good prognosis or fulminant with shock. In the latter group, the mortality is still 25–50% (Peltola, 1983; Halstensen et al., 1987a; Halstensen et al., 1987b). In fulminant meningococcal septicemia, as well as in severe meningococcal meningitis, prompt Pen G administration is life-saving. A primary care physician who suspects meningococcal septicemia should give empiric Pen G or ceftriaxone before the patient is sent to hospital. Similarly, in hospital, if lumbar puncture has to be delayed because a CTscan is to be done first, i.v. antibiotics are warranted before CSF is obtained (Talan et al., 1988; Cartwright et al., 1992; Strang and Pugh, 1992; Hart and Rogers, 1993).

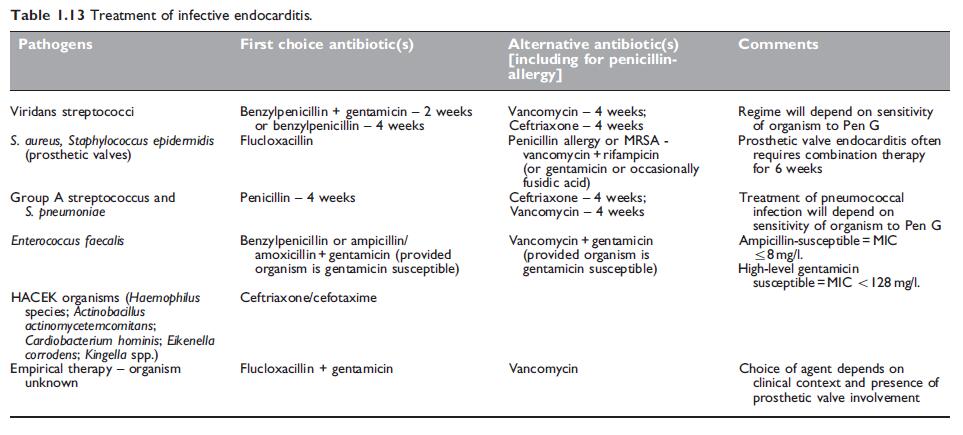

Bacterial endocarditis

Guidelines on the treatment of endocarditis have been issued by the American Heart Association (Baddour et al., 2005), the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (Eliott et al., 2004), and the European Guidelines group (Horstkotte et al., 2004). A summary of treatment options is shown in Table 1.13.

Pen G is recommended for the treatment and prevention of endocarditis caused by viridans streptococci and S. pneumoniae provided the organisms are sensitive (Durack, 1995). Endocarditis due to pneumococcal strains that are intermediate or high-level resistant to penicillin can be cured with Pen G in experimental animal models so long as the Pen G levels are maintained above the MICs throughout the dosing period (Guerrero et al., 1994). It is also indicated for endocarditis caused by group A streptococci and S. bovis. The duration of treatment ranges from 2 to 4 weeks (see Table 1.13). The length of treatment will depend on the nature of the infecting organism and its antibiotic susceptibility.

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Many organisms can be involved in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) but the exact bacteriological etiology is often difficult to determine. Neisseria gonorrhoeae, S. pyogenes, GBS, and anaerobic streptococci are important pathogens which are all, except N. gonorrhoeae, usually Pen G sensitive. Others, such as Chlamydia trachomatis, certain anaerobes including B. fragilis, and Enterobacteriaceae such as E. coli and Klebsiella spp., are Pen G resistant (Goodrich, 1982). Seriously ill patients in whom bacteriologic diagnosis has not been established require combination chemotherapy. Crystalline Pen G in a dose of 12 g i.v. daily may be combined with a tetracycline and an aminoglycoside such as gentamicin. This still does not provide treatment for B. fragilis, so the use of clindamycin or metronidazole should be considered (Burnakis and Hildebrandt, 1986).

Gonorrhoea

Since its discovery, and until recently, Pen G was the preferred drug for the treatment of this disease. However, because of the emergence of strains with chromosomally mediated resistance to Pen G (and also to other antibiotics) and beta-lactamase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (see above under 2b. Emerging resistance and cross-resistance), Pen G is no longer used in most countries throughout the world. In the USA, a single dose of ceftriaxone 250 mg i.m. or cefixime 400 mg orally is recommended (Workowski and Berman, 2006).

Syphilis

Pen G remains the drug of choice for the treatment of this disease (MMWR, 2006). Treponema pallidum has not become increasingly resistant to Pen G, being immobilized in vitro at a maximal rate by only 0.1 mg/ml. Lesions of experimental syphilis resolve most readily in the presence of serum Pen G levels of only 0.4 mg/ml. Early syphilitic infections in humans have been treated successfully with Pen G regimens yielding serum levels of only 0.02 mg/ml. It is commonly stated that the aim of treatment is to maintain sustained comparatively low Pen G serum and tissue levels for 7–10 days.

Yaws

Similar to syphilis, Pen G is the recommended treatment for this disease (Taber and Feigin, 1979). In countries where the prevalence of active yaws is over 10%, the whole population is often given a single i.m. injection of 1.2 or 2.4 million units (0.9 or 1.8 g) of benzathine Pen G. Alternatively, this treatment may only be given to active cases and all their contacts (Brown, 1985; Willcox, 1985).

Leptospirosis

This acute disease is often mild and self-limited, so that the efficacy of antibiotic treatment is difficult to assess. Although leptospirae are sensitive to Pen G in vitro, some consider that this drug (or any other antibiotic) is of little value for treatment of human infections. Most authors believe that Pen G is beneficial provided it is started early in the course of the disease (Taber and Feigin, 1979). A 5- to 10-day course of crystalline Pen G 2.4–6.0 g daily should be given; this usually reduces the duration of pyrexia and also reduces the frequency of jaundice and renal involvement in severe cases, such as those caused by L. icterohaemorrhagiae (Kennedy et al., 1979; Tennent, 1980; Watt et al., 1988). It is important to administer Pen G to pregnant women with this disease as this usually prevents fetal infection (Shaked et al., 1993).

Lyme disease

Described in 1976, this disease presents with skin lesions (erythema chronicum migrans) and often headache, fever, malaise, and fatigue. Some patients develop recurrent arthritis, and occasionally neurologic and cardiac complications can occur (Steere et al., 1987; Dekonenko et al., 1988; Williams et al., 1990; Motiejunas et al., 1994). In the first empirical antibiotic trial, Steere et al. (1980) used oral Pen G for 7–10 days to treat this disease. This shortened early manifestations and fewer patients developed arthritis, but subsequent neurologic and cardiac abnormalities were unaffected. Tetracycline was also helpful, but erythromycin had no significant effect. The discovery that this disease is caused by a spirochete, B. burgdorferi, transmitted by the tick Ixodes dammini (Harris, 1983), explains why Pen G treatment is effective.

Rat-bite fever

Pen G is effective for both S. moniliformis (Actinobacillus muris) and Spirillum minus infections (Raffin and Freemark, 1979). If endocarditis is present, 4–6 weeks’ chemotherapy is advisable (Rupp, 1992).

Clostridium perfringens (welchii) infections

For the treatment of gas gangrene, postpartum infection with C. perfringens, and postabortal C. perfringens septicemia, Pen G has been regarded as the best antibiotic (Dylewski et al., 1989). The use of polyvalent gas gangrene antitoxin as an adjunct to Pen G has been controversial, but most authorities now advise against its use (Dylewski et al., 1989). Gas gangrene may occur in patients with occlusive arterial disease undergoing lower limb amputation, and prophylactic Pen G for 2 days, starting immediately before the operation, should be used (Brumfitt and Hamilton-Miller, 1975; Mashford et al., 1994). For Pen G-allergic patients, either chloramphenicol or erythromycin is a suitable alternative. Pen G-resistant C. perfringens strains have been reported.

Tetanus

Pen G is used in conjunction with antitoxin in the treatment of tetanus. Although C. tetani is sensitive to Pen G, the nature of the infected wound is often such that the organism is inaccessible to antibiotics. The main principles in the treatment of a tetanus wound are surgical debridement and prevention or treatment of associated infection. The latter may lead to activation of spores and create an anaerobic environment (particularly if an undetected foreign body is present) for the proliferation of C. tetani. Pen G is unreliable for tetanus prophylaxis and, in previously nonimmunized patients, human tetanus hyperimmune immunoglobulin should be used. Metronidazole can also be used for treatment of tetanus (see Chapter 90, Metronidazole).

Anthrax

Pen G has been the mainstay of treatment for this disease. However, concerns have been expressed about low-level beta-lactamase activity in some isolates and also the poor penetration of beta-lactams into macrophages (Bell et al., 2002). Ciprofloxacin or doxycycline are now preferred for the treatment of cutaneous anthrax (Brook, 2002). Sixty days of treatment is indicated for pulmonary disease, for which combination therapy with ciprofloxacin plus another antibiotic with activity against B. anthracis (e.g. Pen G, rifampicin) is indicated. Postexposure prophylaxis is indicated with ciprofloxacin or doxycycline (Brook, 2002). Bacillus anthracis can rarely cause bacterial meningitis, which should be treated with an intravenous fluoroquinolone plus Pen G or vancomycin (Sejvar et al., 2005). Anthrax has been used as a bioterrorism agent (MMWR, 2001).

Diphtheria

Pen G is used to eradicate organisms in this disease, but the timely administration of diphtheria antitoxin remains the essential measure. Pen G can also be used to eradicate the diphtheria carrier state. McCloskey et al. (1974) found that a single injection of benzathine penicillin was effective in 84% of carriers, but oral erythromycin or clindamycin was superior.

Actinomycosis

Pen G is the drug of choice for this disease, but owing to the fibrotic, necrotic, and avascular nature of the lesions, large doses for several months are necessary (Spinola et al., 1981). Thoracic involvement occurs in 15–34% of cases; cardiac involvement is rare, but, if it occurs, the pericardium is usually involved. Treatment consists of highdose, long-term Pen G therapy as well as drainage of the pericardial space (Fife et al., 1991). Endocarditis is rare, and Pen G again is the treatment of choice (Lam et al., 1993). Actinomyces can also cause liver abscess. Treatment is usually successful with prolonged administration of Pen G and drainage is needed only in some cases (Miyamoto and Fang, 1993). Actinomyces can also involve the central nervous system, causing brain abscess, meningitis, meningoencephalitis, subdural empyema, and epidural abscess.

Pasteurella multocida infections

This organism may cause wound infections following animal bites such as those inflicted by dogs and cats. However, other organisms, such as various types of staphylococci, alpha-hemolytic streptococci Capnocytophaga and anaerobic bacteria, may also cause infections following animal bites (Goldstein, 1992). Less commonly, Pasteurella multocida can also cause septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, septicemia, meningitis, endocarditis, puerperal sepsis, renal infection, acute epiglotittis, or pleuro-pulmonary infections (Johnson and Rumans, 1977; Lehmann et al., 1977; Mitchell et al., 1982; Raffi et al., 1987; Kumar et al., 1990; Leung and Jassal, 1994). Septicemia is more likely to occur in patients with severe underlying diseases, such as advanced hepatic disease or neoplasms (Stein et al., 1983). Pasteurella multocida infection of a prosthetic vascular graft has been reported (Kalish and Sands, 1983). Pen G is indicated for all of these infections, as this Gram-negative bacillus is usually highly sensitive to Pen G (Weber et al., 1984). Resistant strains occur, but are very rare.

Capnocytophaga canimorses (formerly DF-2 bacilllus) infections

Capnocytophaga canimorses (formerly DF-2 bacilllus) infections are usually acquired from dog bites. In splenectomized patients, often a fulminant septicemia with shock results; in patients with intact spleens the illness is usually milder, but septicemia and endocarditis may occur. Crystalline Pen G, given i.v., is the treatment of choice, but other antibiotics, such as clindamycin, are also effective (Findling et al., 1980; Kalb et al., 1985; Westerink et al., 1987). Beta-lactamasepositive strains have been described (Bilgrami et al., 1992).

References

Abraham EP (1980). Fleming’s discovery. Rev Infect Dis 2: 140.

Acar JF, Minozzi C (1986). Role of beta-lactamases in the resistance of

Gram-negative bacilli to beta-lactam antibiotics. Rev Infect Dis 8

(Suppl 5): 482.

Adkinson Jr NF, Thompson WL, Maddrey WC, Lichtenstein LM (1971).

Routine use of penicillin skin testing on an inpatient service. N Engl J Med

285: 22.

Aharoni A, Potasman I, Levitan Z et al. (1990). Postpartum maternal Group B

streptococcal meningitis. Rev Infect Dis 12: 273.

Aldridge KE, Ashcraft DS, O’Cain P et al. (1998). A multicenter study of the

prevalence and susceptibility patterns of isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae

with reduced susceptibility to penicillin G in Lousiana. Am J Med Sci 316:

277.

Al-Hadramy MS, Aman H, Omer A, Khan MA (1986). Benzylpenicillininduced

neutropenia. J Antimicrob Chemother 17: 251.

Al-Obeid S, Gutmann L, Williamson R (1990a). Correlation of penicillininduced

lysis of Enterococcus faecium with saturation of essential penicillinbinding

proteins and release of lipoteichoic acid. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother 34: 1901.

Al-Obeid S, Gutmann L, Williamson R (1990b). Modification of penicillinbinding

proteins of penicillin-resistant mutants of different species of

enterococci. J Antimicrob Chemother 26: 613.

Anderson AW, Cruickshank JG (1982). Endocarditis due to viridans-type

streptococci tolerant to beta-lactam antibiotics: therapeutic problems.

Br Med J 285: 854.

Anderson MD, Kennedy CA, Walsh TP, Bowler WA (1993).

Prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Rothia dentocariosa. Clin Infect Dis

17: 945.

Andrade RJ, Guilarte J, Salmeron FJ et al. (2001). Benzylpenicillin-induced

prolonged cholestasis. Ann Pharmacother 35: 783.

Andrassy K, Scherz M, Ritz E et al. (1976). Penicillin-induced coagulation

disorder. Lancet 2: 1039.

You may like

Related articles And Qustion

Lastest Price from Penicillin G manufacturers

US $0.00-0.00/mg2025-04-18

- CAS:

- 61-33-6

- Min. Order:

- 10mg

- Purity:

- 98

- Supply Ability:

- 10000000

US $0.37/KG2024-10-22

- CAS:

- 61-33-6

- Min. Order:

- 1KG

- Purity:

- 99%

- Supply Ability:

- 10kg/100kg